It wasn’t my habit years ago to walk into your average office and cringe at the sight of workers sitting at their desks. I have to confess that that sort of reaction is exactly what takes hold of me nowadays.

After seeing many patients that need treatment for everything from numbness and tingling in their fingers to debilitating lower back pain, it quickly became obvious that the desk posture of the average American office worker really isn’t working out. Home computer users needed plenty of help, too.

This article is dedicated to those of us who’ve made the jump to the information age. If you use a computer, read up. You need this information.

We’re going to walk step by step through setting up your computer workspace. You’ll be rewarded with a much less stressful setup that will treat you better long term.

A Good Foundation

We start with your chair. The more adjustable, the better. The base, or seat, of the chair should not only raise and lower, but ideally it should be able to tilt forward and back.

That is, the edge of the base that is closest to your knees should be able to lower relative to the edge that is closest to the back support.

You need the base of the chair higher than you think. You want to be able to raise the base so that your hips are significantly higher than your knees. Say, at least 4-5 inches.

Stand up. Place one hand at the small of your back and the other on your tail bone. Keeping your hands where they are, slowly sit down onto a low chair that has your hips even with your knees. Feel how your lower back rounds out substantially?

Now start over in the standing position. This time, sit down onto a taller chair, stool, or even a tabletop so that your hips are well above your knees.

You should notice that your lower back doesn’t round out as much, keeping your spine in a more neutral position and the weight of your torso centered through your pelvis. When you’re in the right position, even your feet will feel more grounded on the floor.

Here’s where the base tilt comes into play. With your hips higher than your knees, on some chairs the front edge of the base will dig into the backs of your thighs.

Tilting the front edge of the base downward eliminates this pressure, and also has the beneficial side-effect of slightly rocking your pelvis forward into an even better position.

If your chair doesn’t have this feature, you can accomplish the same thing with a small pillow or wedge, with the thick part toward the back.

Now that the base is at the optimal height and tilt, you should be able to sit comfortably, balanced, without the need for any particular back support. This is the reason most people sit with better posture on an inflatable exercise ball.

Sitting on an exercise ball, your hips are typically higher than your knees, and the natural curvature of the ball tends to rock the pelvis slightly forward so that you are balanced over what yoga practitioners call your “sit bones”.

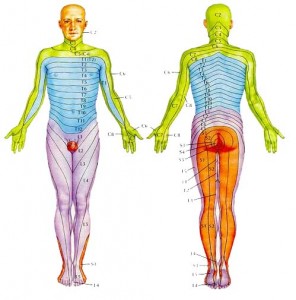

Anatomically these are known as the ischiums, and they make up the part of your pelvis that is closest to the ground. You can feel them simply by putting your hands under your buttocks when you’re sitting.

Balance is key. If our spine is centered over our pelvis, it takes very little energy to maintain good, low stress posture. It’s only when we slouch, lean too far forward, or too far back that we have to engage extra, non-postural muscles to hold our position.

As far as exercise balls go, there’s nothing wrong with using one as your regular “chair” of choice. Most people will prefer the aesthetics and extra adjustability of a well-made office chair, however, so read on.

Gentle Reminders

Now that the base of your seat is at the right height and tilt, you can adjust the back support of the chair. Once you’re sitting in a balanced, tall position, with hips higher than knees, simply adjust the back of the chair until it gently contacts your lumbar area.

The seat back should essentially function as a reminder when you begin to slouch. When you do, your spine will press more firmly into the back of the chair. This additional pressure will serve as your cue to get yourself back into a good position.

The next reminder comes from the armrests. Sitting tall, your shoulders should be relaxed, hanging loosely from your torso. Your elbows should be bent at 90 degrees or more, so that your forearms are angled slightly down from elbow to wrist.

Assuming this position, bring the armrests up so that they gently touch the undersides of your forearms. Once there, if you start to slouch your forearms will rest more firmly on the armrests, and your shoulders will start to sneak up closer to your ears. That’s your wake-up call to get back where you need to be.

The Desk is Next

The base is at the right height. You’re sitting balanced over your pelvis. Your forearms are angled slightly downward. Your wrists are not bent, but are flat and relaxed so that you don’t engage any more of your forearm musculature than is absolutely necessary.

Now, look at your hands. Right where they’re placed is the level that your desk should be. More accurately, this is where your keyboard should be, so your desk should actually be placed an inch or two below that.

Notice that we did not determine what level your desk should be until we got your chair setup exactly as we wanted it. We’re obviously assuming that you have a desk that is capable of having its height adjusted. If not, you have options.

First, you have some room to play with the height of the chair. As long as you keep your hips higher than your knees, and you can tilt the base so that your legs are comfortable, you can raise the chair until your hands rest comfortably at the level of your keyboard.

If your desk is set too high, you may run into a couple of problems. You might not be able to tilt the base of your seat enough to get comfortable. Or, in order to get your hands at the right height you might have to raise the chair so high your feet come off the floor.

In these cases a footstool can be a lifesaver. You can find them at most office supply stores and they’re made for this very reason. Using a footstool your legs will be able to rest comfortably using a chair that is set high enough to get the rest of your body into a good position.

If your chair won’t raise you high enough to get you into the correct position relative to your desk, sometimes a keyboard and mouse tray that slide out from underneath the desk will solve the problem. Consult your local office supply store for options here. If that’s not possible, it’s time to invest in a new chair, desk, or both.

Look Up to Work

The last thing we adjust is the position of your monitor. Don’t skimp on this one. Neck problems that end up causing shoulder, arm, or hand pain are frequently caused by chronically poor head position.

Where do you put it? Right where your eyes go. Place the center of the screen at eye level. You can pick up a monitor riser or even a cantilevered stand to set it at just the right spot. Again, consult your local office supply store. In a pinch, a couple of phone books will also do the trick.

Many “ergonomic guides” that come with computers and monitors recommend placing the top of the screen at eye level. This is too low. Your head will follow your eyes. If your monitor is set on your desk before long you’ll find your neck craning forward so that you can look into the screen.

Finally, make sure the screen is at least a couple of feet from your eyes. Any closer and the constant glare of the screen so close to your face will cause eye strain. Any further and you’ll find yourself bending over your desk to get close enough to the screen to be able to read what is on it.

If you have to use reading glasses or bifocals to see the screen clearly, do yourself a favor and invest in a pair of computer glasses. These are glasses that are designed for computer use.

The entire lens, as opposed to just the bottom half, is devoted to the distance at which you would read from the monitor. This way you’re not constantly tilting your head back and looking down your nose to take care of your daily work.

The Bottom Line

With any setup for a repetitive activity, use your body as a guide. The error often made is in attempting to mold your body to a new task or piece of equipment. This is approaching it backwards.

Always try and position yourself in the most neutral, stress free position and then attempt to adapt your task around it. For this reason it pays to invest in desks and chairs that are as adjustable as possible. This gives you the most freedom to play with different positions and find the one that keeps you at ease.

Investment is an appropriate term here. Anything you’re going to spend hours a day on — for weeks or years at a time — is worth a little extra financially. The return you get in reduced stress, tension, and injury will be well worth it.