in Back Pain / Carpal Tunnel / Neck Pain / Numbness / Posture and Ergonomics / Sciatica / Sleep

Last time we talked about sleep, and how many have a skewed idea of what “normal” sleep is.

From waking frequently in the middle of the night, to only sleeping 4-5 hours at a time, to not being able to fall asleep at all, they somehow think that dealing with these issues on a regular basis just makes it part of the ordinary human physiological landscape.

Shoulder, arm, and hand pain, is another group of common complaints patients mention. Any sort of nagging pain in the upper extremity is also frequently accepted as something that is just “part of getting old” or from some previous injury that can’t be helped. Neither is true.

Often, part of the problem is misdiagnosis. Take Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, for example. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, or “carpal tunnel” as it is more commonly referred to, is a condition that affects the hand and is caused by compression of the median nerve, which runs through a passageway in the wrist, a tunnel formed by bones, ligaments, and fascia.

The median nerve sends signals from the thumb, index, and one-half of the middle finger so that you can feel sensations in those digits. It also supplies stimulation to small muscles that control some motions in these same fingers. Sensation and movement on the pinky side of your hand is controlled by the ulnar nerve, which does not pass through the carpal tunnel.

That last point is key. The median nerve runs through the carpal tunnel. The ulnar nerve does not. This means if you experience pain, tingling, or numbness in your entire hand, the problem can’t be originating solely in the carpal tunnel!

It is much more likely that the problem is coming from an area that is affecting both of these nerves simultaneously. Yet we frequently see patients in the office with pain or numbness in their entire hand who have been diagnosed with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

Even worse, surgery is often recommended and performed on these patients, inevitably and unfortunately resulting in no relief from their symptoms. Simply understanding how the nerves are anatomically positioned — the “wiring diagram” of the body, avoids many problems with misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

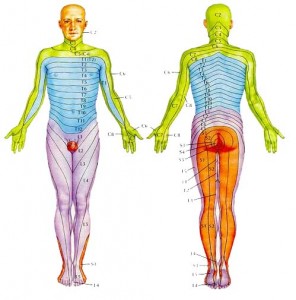

Understanding these relationships is important for complaints besides hand pain. Nerves that supply our extremities originate from the spinal cord in large bundles. As they travel farther away from the cord they branch into smaller and smaller segments, splitting up to cover areas of skin, muscle, and other tissue. The closer to the cord a nerve gets caught, compressed, or otherwise irritated, the larger the area of potentially affected tissue.

Many people are familiar with the radiating pain down the leg commonly called “sciatica.” This pattern of radiating pain from the spine down an extremity doesn’t just occur in the legs. I frequently see patients with symptoms in their shoulder, arm, or hand that originate in the neck. The culprit is the same as in the lower extremity: something around the spine impinges the nerve root that supplies skin and muscle further down.

Pain, tingling, or numbness is thus experienced at a place distant from the source of the problem. Biomechanical relationships in the arm are also altered which can add further irritation to any joint or muscle in the area.

Again, understanding the anatomy is crucial. Just like in the lower back, in between each vertebrae in the neck are discs with a fibrous outer ring and gel-like material in the center. Nerves come out of the spinal cord between the vertebrae, right where the discs are. This means anything that might cause the disc to bulge or herniate has the potential to affect the nerve root.

The nerves in the neck supply the muscles of the arms and provide the skin’s sensations in predictable patterns called dermatomes.

Doctors can use this knowledge to help determine what nerve root might be affected with someone experiencing, say, hand pain in their thumb and index finger.

Take another look at the dermatome photo. Pain in this area, in addition to simply being a problem local to the thumb, could also originate around the 6th cervical vertebra. Your doctor should be able to distinguish between the two.

Aside from the more obvious causes of shoulder or arm pain — falls, sprains, etc. — the most common cause of upper extremity pain I see in the office is habitual. That is, something we do every day as part of our normal routine or posture can bring about aches, pains, tingling, or numbness that seems to have no particular cause. This is prime fodder for the “I’m just getting old” or “I must be out of shape” explanations that float around the water cooler.

In particular, poor neck posture seems to be a major culprit. Anything that routinely brings the chin closer to the chest seems to lead to the type of pain described. Bringing the chin closer to the chest flexes the vertebrae in the neck forward. This position creates wedging of the vertebrae, with the front edges closer together and back edges farther apart.

Remember the discs between each of the vertebrae? When this wedging happens, the discs have to go somewhere. Being more fluid in nature, with the vertebrae wedged together in the front, the discs tend to push out toward the back. If this happens over a long period of time, eventually the discs can bulge or even herniate.

When any of this disc material — or any other anatomical tissue, for that matter — starts to abnormally push on a nerve, it’s a problem. The nerves at this level supply everything you can think of in the upper extremity. Shoulder pain, elbow pain, tingling down the arm, or pain in the wrist and hand are all fair game, to name a few.

So what qualifies as a bad habit? Reading in bed or watching TV with your head propped up. Routinely using a laptop or even a desktop computer with the monitor too low. Long periods of studying or writing with the material on the desk under your chin. Handwork, such as knitting, done with your hands close to your chest. Sleeping on your back with your head on a pillow that is too high, or on your side, curled up tightly in the fetal position.

There are many others. The bottom line is: if you keep your chin down close to your chest for long periods of time doing anything, you have the potential for this sort of problem.

The good news is that fixing this problem is generally not complicated as long as you find someone who can properly diagnose what’s happening. Once you’ve done that, treatment is relatively straightforward.

Chiropractic adjustments help tremendously. The adjustment has to be done in a position and direction where the nerve root is not impinged in any way. When done properly, this seems to clear the nerve root of any impingement and minimize any radiating symptoms experienced.

But the adjustment isn’t the whole fix. Lifestyle habits must be changed. In other words, keep your chin up!

This is crucial to keep the vertebrae aligned and free of any wedging so that things have time to heal. This is analogous to having your skin cut with a knife. The wound will heal cleanly with minimal scarring if it is dressed properly and the edges are held closely together with stitches.

On the other hand, if every day you go in and spread the wound apart with your fingers, you’ll be left with a nasty scar or, worse, the wound won’t heal at all.

Once the adjustment is made and lifestyle habits are addressed, residual issues can be tackled. Long periods of time with poor or diminished function and improper biomechanical support to tissue in the shoulder or arm can leave joints inflamed and muscles gnarly. Get in with a good Applied Kinesiologist, Rolfer, or massage therapist to work out the kinks.

Don’t let anyone tell you that the types of pains I’ve described here are a “normal” part of life. Keep your detective cap on and take an inventory of your usual activities that could be contributing to your condition. With a little persistence you can pass up that “normal” life for an optimal one!